Weak Economy, Weak Currency?

Why a weak economy doesn’t always result in a weak currency.

Before understanding how a weak economy can lead to a strong currency, lets determine what defines a weak economy. The most pertinent measure to consider when measuring an economy’s strength is Gross Domestic Product (GDP). When looking at GDP from an expenditure approach it is made up of government spending, consumption, investments, and net exports (exports minus imports). A weak economy would be defined by consistent contractions in GDP when comparing data readings, while a strong economy will reflect increases in GDP Data.

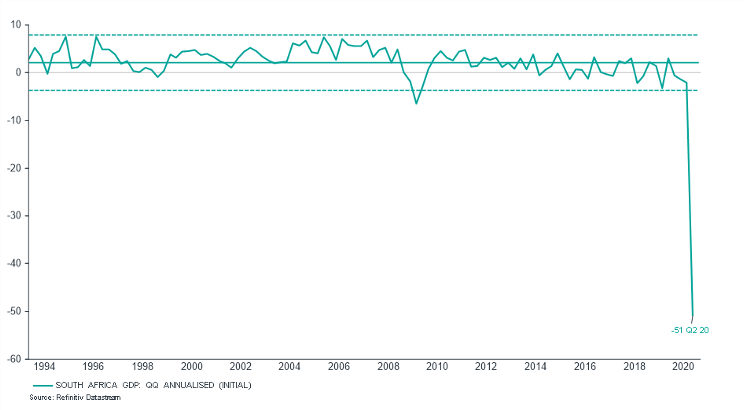

South Africa’s (SA’s) Q2 GDP data was released on Wednesday 08th September. It indicated a staggering contraction of 51% quarter on quarter annualised. This fourth consecutive quarterly contraction in GDP data confirms that South Africa is indeed in a recession (defined as two successive quarters of contraction). Stats sa, who are responsible for GDP data publications, highlighted that this drastic contraction can be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown. The below chart puts in perspective the massive second quarter decline experienced in SA when compared to previous readings.

South Africa GDP: Quarter on Quarter Annualized

The most recent GDP contraction highlights the weakness of the South African economy; however, this weak economy does not necessarily translate into a weak currency. Understanding currency strength is fairly simple as it is determined by supply and demand dynamics. High demand paired with low supply will result in a stronger currency, whereas low demand and high supply will result in a weaker currency.

From an investment perspective, foreign holdings of local investments have plummeted recently, mainly due to the credit rating downgrade and global risk off environment. Earlier this year the last credit rating agency to have an investment grade rating on SA, Moody’s, downgraded South Africa’s credit rating to junk status. This caused the FTSE World Government Bond Index (WGBI) to exclude the country from its investment list and therefore forced significant foreign outflows from the bond market, resulting in fewer foreign holders of SA bonds. We note that in the time since the exclusion, foreigners have begun to purchase SA bonds again. This has resulted in a return to pre-exclusion levels, therefore foreigner held assets are not as low as originally expected.

These outflows were compounded by the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a global risk off environment. Risk off refers to an environment where investors disinvest from risky assets in favour of more stable ones in an attempt to protect their capital. Usually this move directs flows away from emerging markets in favour of developed markets, further reducing foreign holdings in SA. The SA market was able to weather these outflows, and now the rand stands to benefit as there will be fewer dividends and/or interest payments that will require repatriation to their foreign owners. With specific regard to dividends, not only are there fewer offshore holders to which dividends are being paid, but the size of the dividends has also reduced in the face of the pandemic. This means fewer rand sales, giving the currency yet another opportunity to strengthen.

Significant disinvestments from SA bonds and equities as well as SA consumer pressures resulted in liquidity pressures on the SA Economy. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) was quick to respond to these liquidity requirements at the start of lockdown. The SARB effectively turned their focus to spending cash locally and providing liquidity rather than their usual purchasing of dollars to increase their foreign reserves (and subsequently selling rands). In the absence of the usual rand sales headwind due to this shift, the rand will have the opportunity to strengthen.

A weak economy often correlates with high bond yields. Currently SA is offering a significant yield premium with the repo rate at 3.5%, and the 10-year bond offering 9.27% compared to the likes of developed markets offering significantly lower if not negative rates. The reason for the lower global central bank rates is because the pandemic saw most central banks using rate cuts to support and stimulate economies. More attractive local rates mean that fewer local investments will be leaving SA in search for yield, therefore fewer rand sales and potential rand strength. The same goes for many collective investment schemes, pension and provident funds, the majority of which have been at their regulation 28 offshore maximum (30%) for a while now. This regulatory limitation means that they will no longer be able to continue buying dollars to keep the rand weak.

Fewer foreign holdings, smaller dividend payments, reduced ability to increase offshore exposures for many collectives and pension style funds, the higher local yield attracting SA investment and the SARBs liquidity activity; combined with the current weak economy based on GDP data illustrate how a weak economy can translate into a stronger currency.

Please note: This article is based on data up until 11/09/2020.